The opioid addiction problem in the United States continues to escalate at a disturbing rate. One of the factors fueling the use and abuse issue is the amount of opioids prescribed to patients suffering from chronic pain. According to The New England Journal of Medicine, opioids are the most commonly prescribed class of medications in America. Between 1991 and 2013, the number of prescriptions for opioids rose from roughly 76 million to about 207 million, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

More than a quarter of Americans have acute or chronic pain, and the incidence is as high as 40% among older Americans. Educating patients and the medical community about alternative options to using opioids to treat chronic pain has been a slow process, says Allen Burton, M.D., medical director at St. Jude Medical. “It took 15–20 years to get where we are today in using opioids; now we have to undo that.”

Chronic pain can be a result of a variety of disorders, from fibromyalgia to headaches to cancer to joint pain to back pain, which is one of the most common causes. Although prescribing medication, and specifically opioids, can be useful in many circumstances, there are also cases in which medical technologies have the potential to more effectively help patients manage chronic pain.

In a discussion with MedTech Intelligence, Burton talks about the chronic pain issue surrounding spinal pain, comparing neuromodulation therapy to the use of opioid medication. Note, St. Jude Medical currently markets spinal chord stimulators to treat chronic pain.

MedTech Intelligence: What is the current landscape of opioid addiction in America?

Allen Burton, M.D.: Opioid addiction is a part of the issue. There’s chronic opioid therapy, chronic opioid dependence, opioid addiction, and people with mixed problems who use opioids medically or are dependent on them where they may have addictive tendencies or overuse them. We’ve seen a surge in clear addictive behavior, which is complete non-medical use of opioids, and the use of non-prescription medications, such as heroin, are also on the upsurge.

There’s a huge problem with patients who are started on opioids for therapeutic reasons but then get into trouble because [the medications] lose their effectiveness or the patient self-escalates dosage; or, they get into problems with addiction or combining it with other substances like alcohol or other co-sedative medications.

MTI: For patients with chronic spinal issues, what medical technology alternatives are there to opioid treatment?

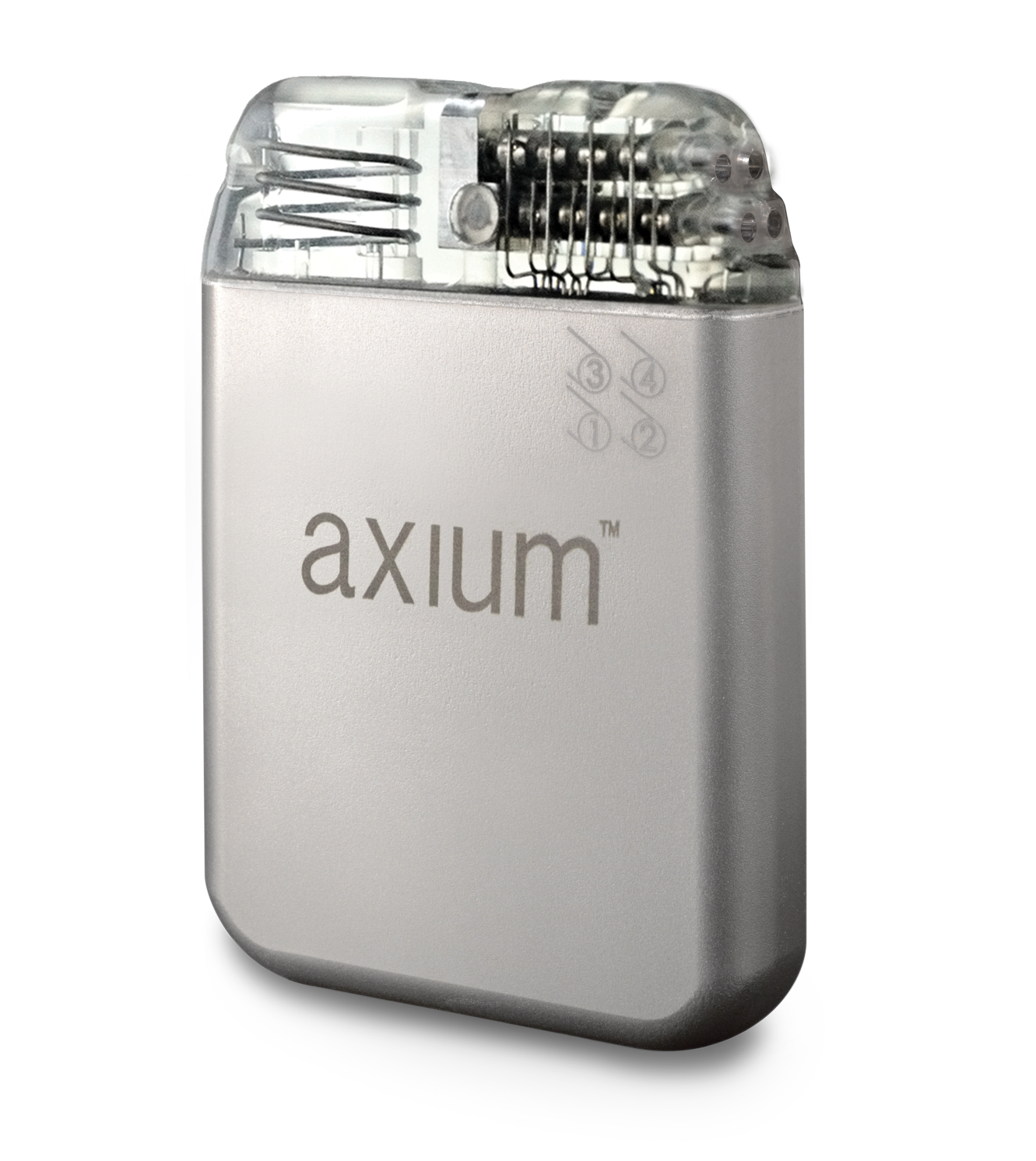

Burton: I think a large percentage of patients suffering from ongoing chronic pain issues have spinal problems, and their chronic pain hasn’t gotten better in spite of attempts at corrective medical procedures. Oftentimes these patients have had surgery for their primary problem (i.e., a degenerative disc, narrow spinal canal or a herniated disc) but still have ongoing, persistent pain. In that setting there’s a therapy called neuromodulation therapy: Modulating nervous input to the brain through small electrical leads placed near the affected nerve, usually in the epidural space near the spinal chord at various locations in the back. The leads are connected to a small, implanted battery device that looks like a pacemaker. This device is set to alter the pain signals that go from the peripheral nerve into the spinal chord and up to the brain. When the electrical energy is applied to that region, it alters the signal, so the brain either feels a pleasant sensation or no painful signal at all.

MTI: What is the cost associated with using neuromodulation technology for pain management versus taking medication?

Burton: If you look at how much a spinal chord stimulator itself costs, it appears to be really expensive—about $15,000–$20,000. Then it needs to be surgically implanted, and there are a lot of variables—where the patient lives, their insurance coverage, and whether the procedure is being done in a surgical center or hospital setting. On its own, this number looks gigantic, but if you compare it to a conventional back surgery or spinal fusion, it becomes very comparable, and it’s actually less expensive than a spinal fusion.

If you start looking at medical therapies (a pill or pain patch), one or two pills look cheap compared to buying a $20,000 device. When you realize that the patient [may be] 35–40 years old and will live to be 75 years old—the patient has 30 years to live with this pain. Take the implant cost and amortize it over the longevity of the device and compare it to medication the patient takes on a daily basis and probably purchases on a monthly basis, and some of the medication costs can be quite significant.

A lot of different health outcomes work has been done on this. [Burton notes that Duke University and St. Jude Medical are working on projects in this area.] Often if you compare a patient who is stable on medicines versus an implant, if the implant is effective and replaces the medicine, usually the break even point (where you spend enough money on the medications where you could purchase the device with the same amount of money) is between 18 months to two years.

In addition to the devices bringing the patient’s medication burden down, the other cost savings when you get the pain under control is that the patient no longer seeks specialty care. They no longer go surgeon to surgeon for further back operations; they stop going to ERs because their pain is out of control. So yes, these are expensive devices when you compare them to nothing, but when compared to ongoing care for pain that is somewhat out of control, the cost will actually be quite reasonable. You actually save money if you get the pain under control with an implanted device.

MTI: What would you say to patients or physicians who have the mindset that it is easier to take a drug versus having surgery, especially involving an implant?

Burton: A lot of patients and primary care physicians make that assumption. When people start on chronic opioid medications, it’s often [prescribed] by the primary care physicians without a discussion about the risks and benefits of the medicines. And the patient is begun on sometimes a multi-year or multi-decade of ongoing use of pain medications, which gets quite cumbersome and complicated—the patient becomes dependent and, in some cases, addicted to the medicines. They can cause a long laundry list of side effects, and then there’s the question of their effectiveness. There is very little evidenced-based medicine involved in ongoing use of the pain medications. The FDA only requires a short period of follow up to approve drugs, and patients often take them for years or decades. They often become tolerant to the medicines, which lose their effectiveness over time, and sometimes in an effort to recapture the pain, there’s a gradual titration of the medication dose up. So the patient has decreasing therapeutic effect from the medicine, and they actually start taking increasing doses, and this sometimes leads to a dangerous circumstance where they’re taking a large dose of medication with a very limited therapeutic effect. The expense involved can be significant on an ongoing monthly basis in spite of this gradually reducing effect of the medication.

The spinal chord stimulator procedure has broad indications for chronic pain of the trunk and the extremities—so it has wide applicability across many chronic pain states. There’s a percutaneous trial period in which a relatively simple procedure is performed—almost like an injection, with light sedation and a needle, under imaging of the spine. Instead of a medication, wires are placed through [the needle] and secured temporarily to the patient. Over a one-week period, the patient can experience the therapy. It’s almost like the patient gets to test-drive the spinal chord stimulator before they say they want it implanted.