Most of the time development of a medical device seems a rational process with little room for creativity and form. Problems are solved by generating new technologies or functionalities and a lot of time is spent on engineering or in the lab, followed by validation and implementation. Safety and efficacy are the prime drivers, these new innovations must reach the market in the shortest time possible and so form seems to follow function almost immediately. However, a product’s form and its function have a much deeper and stronger relation than one might assume.

During the process of developing medical products, the form of a product takes shape while it is being framed from different perspectives. Significantly and usually unknown to the users and even the developers at times, the form of the device is critical to achieving the outright goals of efficacy and safety. In some cases more significantly than the technology itself.

Form versus usability

New solutions and innovations are being developed and introduced at an increasing speed. The products we use keep changing their appearance and new applications present themselves to us every day. The way we use these products is no longer related to what we have learned at school or university and we trust our intuition more and more. The usability of a new product depends largely on the clues and cues the product can give us. Very often there is not enough time for training or user manuals. At those times it is important that form supports the use. When developing new medical instruments, we design the shape of the instrument so that it will support the user in maneuvering the tool and controlling the procedure. The form will guide the user by sight, touch and maybe even sound. Ask anyone about to undergo surgery how important a surgeon’s control of his or hers instrument is,’ I am sure we know the answer. The same applies to point of care IVDs , where it is well published that usability, not the lateral flow technology itself, is responsible for most errors in diagnosis. (2) Lee, Vernon J, 2007)

Form versus user experience

A product’s function and its effectiveness in helping the user achieving his goals is very much influenced by the way it is experienced by its users. How quickly a patient will recover is influenced by the experience he or she has receiving the treatment. One of the most important tools we have to prevent mistakes or misunderstandings in use of a product is by designing for the right experience.

A product’s function and its effectiveness in helping the user achieving his goals is very much influenced by the way it is experienced by its users. How quickly a patient will recover is influenced by the experience he or she has receiving the treatment. One of the most important tools we have to prevent mistakes or misunderstandings in use of a product is by designing for the right experience.

When designing a drug delivery device, during use observations designers noticed that the patient was very uncomfortable at the sight of the large needle. This was solved by creating a special shaped housing, blocking the view on the needle for the patient, while still enabling sufficient view for the doctor. This way the form supported the user experience and made a more efficient and less stressful procedure possible.

When designing a drug delivery device, during use observations designers noticed that the patient was very uncomfortable at the sight of the large needle. This was solved by creating a special shaped housing, blocking the view on the needle for the patient, while still enabling sufficient view for the doctor. This way the form supported the user experience and made a more efficient and less stressful procedure possible.

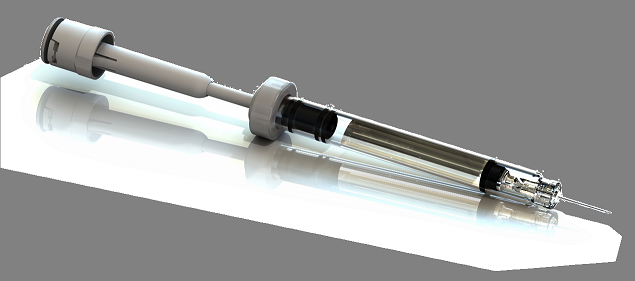

We came across a similar case designing a pre-filled retractable syringe. One of the important factors we implemented was that we designed the product such that the needle was visible when retracted so that when the injection was over, the patient and user (clinician) knew the needle was safely back in the barrel and not in the patient’s body. A competitor retractable syringe did not do this and the nurse had to take the patient to X-ray because she thought the needle was still there.

We came across a similar case designing a pre-filled retractable syringe. One of the important factors we implemented was that we designed the product such that the needle was visible when retracted so that when the injection was over, the patient and user (clinician) knew the needle was safely back in the barrel and not in the patient’s body. A competitor retractable syringe did not do this and the nurse had to take the patient to X-ray because she thought the needle was still there.

Form versus behaviour

The form of a product can also be used to “guide” the user behavior. A curved pathway will guide people around dangerous objects. An organic shaped handle will lead a person’s hand to the correct button without having to look at the product. This enables the user to keep his eye on the actual procedure. Form can “nudge” the user and in this way influence the interaction between product and user. This has shown to be a very effective way of designing improved use interaction. (Dorresteijn, S. (2012)2)

Form versus function

The products we develop show us how important Form is and how it influences Function. Besides the viewpoints described, Form relates to many others like brand, culture and mechanical constraints. Addressing these different perspectives and translating what you see into integrated future products, is what true product development is about.

References:

- Lee, Vernon J, et.al., User Acceptability and Feasibility of Self-Testing With HIV Rapid Tests, 1 August 2007 – Volume 45 – Issue 4 – pp 449-453, JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318095a3f3, Epidemiology and Social Science

- Dorrestijn, S. (2012), The design of our own lives: Technical mediation and subjectivation after Foucault. Enschede: University of Twente (PhD thesis).