UL’s human factors engineering team has conducted usability tests of dozens of injection devices involving a cumulative total of more than 1,000 individual tests sessions. Test participants have included laypersons with widely varying demographic traits, as well as clinicians who train patients how to self-inject and/or to administer medication to a patient.

This extensive usability testing experience has taught us much about how to develop an injection device that enables people to inject medication safely and effectively.

Lesson 1: Apply Human Factors Engineering Throughout Development

To ensure device safety and effectiveness in the hands of the intended users, injection device manufacturers should invest in human factors engineering (HFE) to produce a truly user-friendly device. Meeting the HFE expectations and requirements set forth by regulators in many regions will be a necessary, parallel benefit.

Investing in HFE from an early stage of development helps ensure that an injection device matches users’ capabilities, needs and preferences. Predictable returns on an HFE investment include increased device intuitiveness, reduced chance of users committing potentially harmful use errors, and greater user satisfaction.

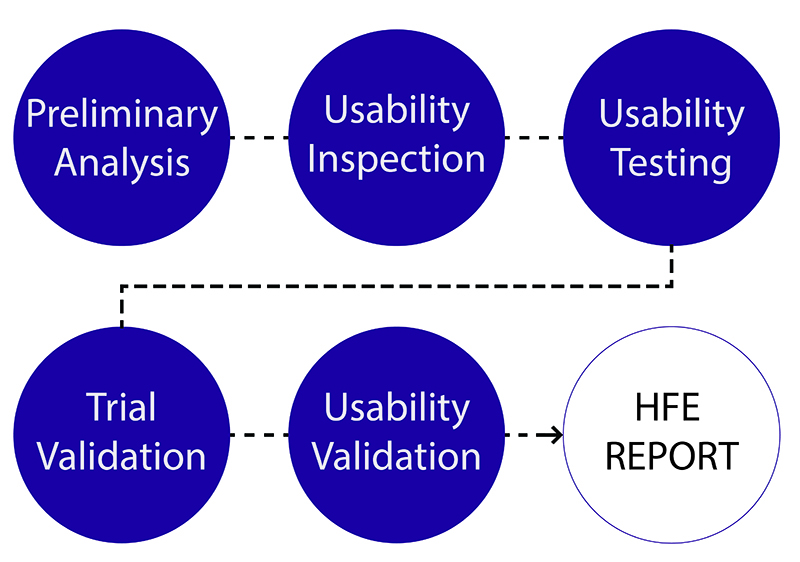

Major HFE activities include:

- Interviewing and observing intended users as a basis for formulating user interface requirements

- Analyzing how users interact with a device prototype to identify potential use errors and design mitigations

- Conducting usability tests to determine a preferred design concept, refine its injection device’s design, and ultimately validate that users can use it safely and effectively.

Lesson 2: Avoid These Specific Use Errors

- Looking across thousands of usability tests sessions, we have observed that myriad injection devices fall victim to many of the same use errors. Below are some of the most common ones associated with a potential for harm, and the more prevalent user interaction failures that manufacturers should guard against, ideally through intrinsically safe design as opposed to labeling and training.

- Users hold an injection device upside-down, placing them at risk of injecting their hand (typically, the thumb) when initiating an injection. The use error is usually induced by inadequate orientation cues, including the needle end of the device looking like a button to press.

- Users do not hold the needle in the skin (this is typically simulated using an injection pad) for the necessary duration (e.g., 5–10 seconds). Rather, users remove it when the device makes a noise or provides tactile feedback that is misinterpreted as an indication that the injection is complete, even though the needle should remain in the skin to ensure a thorough infusion of the drug.

- Users risk a needlestick injury by recapping a used needle. Such an injury may only cause discomfort to someone who is self-injecting, but could transmit a blood-borne disease or cause a bacterial infection in the event that a caregiver is injecting someone else.

- Users overlook that the injection device is past its expiry date, typically because the date is printed in small characters, has an unfamiliar format (e.g., European format viewed by an American), and/or is in an inconspicuous location.

- Users do not effectively inspect the drug for various forms of contamination and deterioration, perhaps because the “viewing window” is so small that it is overlooked or, if noticed, does not provide a clear view of the drug within the device’s reservoir.

Lesson 3: Minimize User Interactions

One way to avoid use errors is to minimize the number of steps users must perform during device use. Simply stated, eliminate and automate functions wherever possible unless doing so induces other errors or confusion about the device’s operation. For example, a developer could eliminate the need to prime an injection device, lockout its use after the expiration date, and automatically protect the needle after its use so that recapping is unnecessary.

Lesson 4: Provide Excellent Instructions

- As stated above, the best way to protect users from making mistakes (i.e., committing use errors) is to design an injection device that requires few user interactions, is intuitive to use, and includes the appropriate safeguards. Then, you can augment with excellent instructions for use (IFU). Although some users will disregard an IFU, others will depend on it to varying degrees. Therefore, manufacturers should produce the best possible IFUs, reflecting the following characteristics:

- Use graphics to reinforce important textual directions

- Differentiate each procedural step from other, supplemental information

- Limit the amount of information conveyed to avoid oversaturating users

- Write text instructions in the active voice and use terms that users will understand

- Use color in meaningful ways to increase clarity to draw attention to key device interactions and add clarity to the instructions

- Use text that is sufficiently legible for the intended users, some of whom might have visual impairments

- Establish an information hierarchy that draws attention to the most important information

- Co-locate warnings with the related instructions, perhaps in addition to a consolidated, separate list of all warnings

- Convert a single sheet IFU into a booklet if there is too much information to convey on a reasonably small sheet with legible (i.e., sufficiently large) text, sufficiently large and detailed graphics, and a modicum of blank space to separate groups of related content

- Package the instructions in a manner that draws the users’ attention or even forces users to handle them, thereby preventing the instructions from being overlooked

Lesson 5: Conduct Multiple Formative Usability Tests

Injection device manufacturers should conduct multiple formative usability tests before conducting a human factors validation test. Such tests should include the full array of intended users—this might include representative patients, caregivers and clinicians. Within these three sample groups, there might be sub-grouping based on age, receipt of training to use the injection device, and degree of past experience performing injections. We assert that conducting preliminary usability tests are the best way to identify an injection device’s strengths and opportunities for improvement and, when iterated with design, improve a device’s interaction quality. In lieu of preliminary tests, manufacturers almost always discover a “showstopper” during a validation test that costs considerable time and money to remediate.

Conclusion

Manufacturers are well served to apply HFE early and throughout the injection device development process. They can expect to produce a device that is demonstrably safe and effective from a user interaction perspective. Such devices are more likely to obtain clearance for sale on the first try because manufacturers can present regulators will compelling evidence that their device can be used safely and effectively by the intended users.