FDA’s expectations related to human factors are about to get a significant revamp with the release of its latest guidance on the topic. The changes are fundamental, signaling the agency’s renewed focus in this area, and it will affect medical device submissions.

What Has Changed?

The draft guidance, “Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Optimize Medical Device Design“, was released in 2011 with publication expected later this year. It was developed by the FDA Human Factors Premarket Evaluation Team, which worked closely with the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI).

Medical device human factors and usability engineering has been largely based on IEC 62366:2007 and HE75:2009 analytical techniques. These methods identify and characterize user populations and workflow through tools such as workflow analysis, and ergonomic and anthropometric data in an attempt to mitigate risks associated with both normal and abnormal use. Though they remain an important foundation, the scope of the new guidance goes beyond the analytical and requires early practical evaluation through exploratory human factors/usability studies. Key to this approach is that development is iterative with design decisions practically tested to Identify issues not discoverable through application of analytical techniques.

Practical evaluation with representative users resulting in iterative development is key. The FDA wants to see your device in the hands of users early in the development process undergoing simulated‐use testing to discover and explore unanticipated hazards. They want proof that development is based on user feedback and observations to confirm that the device can be used safely and effectively.

What is the Evolved Process?

The process and FDA perspective on human factors and usability engineering can seem like an intangible part of development to many in the medical device industry. It is often led by qualitative data rather than tangible and comfortable quantitative data. The word comfortable is used here for quantitative because development that is based on using quantifiable measurements and a process that is repeatable, provable and defendable will result in definite actionable design decisions.

In contrast, it is uncomfortable to base design decisions on qualities that are descriptive, user specific and often immeasurable, as the data is idiosyncratic and subjective by nature. The FDA’s focus in its draft guidance has been to include contemporary concepts of usability engineering in a process that is repeatable, provable and defendable to produce definite actionable decisions.

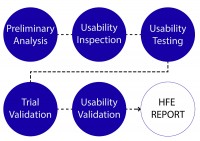

The evolved process can be defined in six distinct phases: Preliminary analysis, Usability inspection, Usability testing, Trial usability validation, and Usability validation.

The result of all of these phases is a Human Factors and Usability Engineering (HFE) Report to be included in the Design History File (DHF). While many expectations remain unchanged from the existing FDA perspective, new areas of focus emerge as is discussed in this article.

Preliminary analysis. Part of the formative evaluation, this is the foundation for usability research and the basis for initial concepts. It is comprised of analytical-based research that focuses on identifying relevant standards, user populations, characteristics, limitations, use environment, initial work-flow and critical task analysis. From this we are able to define usability goals and outputs. Formerly a major focus of the FDA’s expectations (yet still an important aspect of usability research), the agency has shifted its attention, as analytical-based research cannot identify and explore many device-specific usability hazards.

Usability inspection. Using the foundation built in the preliminary analysis, this first usability exploration is from the user’s perspective. The phase relies mostly on design heuristics and user/key opinion leader perspectives. The activities are exploratory, often utilizing interviews, site visits and low-fidelity prototypes. This task is essential in populating a product requirements document and understanding specific user needs.

Usability testing. Key to the revised guidance, usability testing commences the iterative process of design refinement and testing. It is based primarily on exploratory human factors/usability studies to identify issues not findable through analytical techniques. Physical assets ranging from low-fidelity prints to analogous rigs and 3-D prototypes are essential to this phase. This testing should be conducted early in the mechanical engineering effort to mutually inform decisions and control iterative developments and budgets. FDA wants your device in the hands of users from an early stage using simulated‐use testing to discover and explore unanticipated hazards. Then retest any of the decisions you have made based on discoveries to confirm that the efforts were successful in improving device safety and efficacy.

Pre-Validation Testing. This phase acts as a trial prior to formal validation testing allowing for minor design changes before a final design freeze. It marks the conclusion of formative testing and the initiation of summative validation testing, with major usability risks mitigated and final usability specifications identified. This exercise is not always required; however, it is an efficient way to catch minor issues that may arise during formal validation testing at a cost-effective stage in development. As users are not always predictable, neither are all use-related issues. This phase is highly advised, especially where clinical or human trials are required.

Usability Validation. This final validation testing provides the primary usability evidence in accordance with FDA’s expectations. To fulfill validation testing, a number of critical elements must be considered. You must demonstrate the design is safe and effective for use within its intended or simulated environment under both realistic and challenging scenarios, with a representative sample of the end-user population. The focus of the testing is to validate that the design is adequate for critical and essential tasks performed by the user while proving the effectiveness of any usability risk mitigations. Data is collected through observation within a defined methodology and protocol. It includes user perspectives during tasks and post-testing interviews.

HFE/Usability Report. The HFE report forms part of the DHF. It is the main tool to communicate to your auditor and the primary reporting tool to address regulatory requirements. It is a record of the usability development process (method and rational), and how design decisions were tested and implemented. This document is vital to successfully gaining regulatory acceptance. Even the best human factors developments can be overlooked or viewed as a possible risk if not reported correctly.

What Does This Mean to Your Process?

Human factors and usability engineering regulatory expectations have been defined by the FDA Human Factors Premarket Evaluation Team and AAMI in a comprehensive, definitive and progressive process. Relying on tangible data, and basing development decisions on assured design inputs, will help ensure your products’ success through the regulatory process and in the market.

Our recommendations. Engage early with human factors in your development process. Mutual development with other disciplines will reduce iterations in development helping control budget and possible risk while ensuring better efficacy. Allow for a reasonable time and budget within your development to fulfill the expanded regulatory expectations. Give human factors and usability a voice in your development—it may well give you the market edge.

HFE Impact on Cardiovascular Bioprosthesis MarketOnce seen primarily as a form of risk mitigation, human factors and usability engineering is now proving to be an asset in creating market-leading products. One such area is within Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI). The cardiac bioprosthesis market has seen considerable development in the past two decades. Despite the vast and often beautiful mechanical development conducted on the bioprosthesis itself, the usability of the deployment device is proving to be the market differentiator. It is now recognized that placement of the valve has a dramatic effect on patient outcome.1 Improved deployment devices will be required to achieve this outcome. Designs that mitigate or reduce major deployment risks, which are intuitive, accurate and efficient to use, are taking the lead in the market. Ultimately, designs in which human factors and usability engineering have had a strong voice in the development stage are proving to have better clinical outcomes and quality of life for patients, while creating market-leading products. It is a strong tool in any process. Give human factors and usability a voice in your development, it may well give you the market edge. |

Reference

- Sinning, J.M., Werner, N., Nickenig, G., & Grube, E. (2012). Next-Generation Transcatheter Heart Valves: Current Trials in Europe and the USA. Methodist Debakey Cardiovascular Journal, 8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3405796/

Additional Resources

- Tools to Select the Right Concept in Medical Device Development, by Mark Drlik

- 5 Top Annual Plan Medical Device Design and Development Process Improvements, by Scott Phillips