Steve Arless grew up in a Lebanese immigrant family in Montreal. His father was an accountant. His mother’s brother was an entrepreneur, and she always encouraged him to think about business. But Steve went a different way. He studied engineering and chemistry at McGill University. Upon graduation he got a good job at Smith and Nephew where he spent 17 years learning the industry and how to build and motivate sales and marketing teams. His last five years were as CEO of North American Operations. Then the opportunity to join a small crazy start-up came along with a vision of doing cardiac therapy with cryogenic balloons. The family heritage came to the surface. He sold his house and jumped in with both feet. It was a wild ride. He raised $160 million. At least once he had to halt a clinical trial mid-stream and raise more money to do it again. The company went public, hired 350 people, and launched the CryoCath product. A few years later it was sold to Medtronic for $400 million.

“When I won the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award, all I did was thank my mother,” said Arless, fresh from the sale of another start-up company, CardioInsight Technologies.

Once an entrepreneur, always an entrepreneur, right?

Source: US Patent and Trademark Office (Click to enlarge)

Coming from an entirely different direction, Thomas Fogarty grew up modestly in Cincinnati. His first career idea was boxing. When that didn’t work out, he entered Xavier University under probation where he attracted a prominent mentor and then went on to graduate with a medical degree from the Cincinnati College of Medicine. As a surgeon, he was appalled to see the morbidity and mortality associated with embolectomies to remove peripheral arterial blood clots and came up with the idea of using an inflated bladder catheter pull them out (see Figure 1). His first prototypes were hand tied using rubber gloves and fly-tying techniques. Eventually he was able to persuade a small company, Edwards Laboratories, to make them commercially. From there, Fogarty founded 33 medical device companies and a venture capital company while maintaining a clinical practice and teaching at Stanford University.

Other serial entrepreneurs, such as Alfred Mann, studied science. But which is the most common path? If you want to influence the odds of success in medical device entrepreneurship what should you study, and to what level? And, how should you start your career?

To answer these questions, a few years ago I started interviewing successful serial medical device entrepreneurs. Then I began assembling data from people I identified through Google or LinkedIn searches. I put together an early and validated set of 50 entrepreneurs who had started at least two medical device companies and gathered information about their education, careers, patents, companies and other interesting facts (see Table I).

| Prolific Founders of Medical Device Companies | |||

| Thomas Fogarty | Rudy Mazzocchi | David Benaron | Michael Berman |

| Mir Imran | Josh Makower | Mike Gertner | Ram Rao |

| Alfred Mann | David Fischell | Amar Sawhney | Michael Baker |

| Michael Henson | Fred Khosravi | Jack Lloyd | Amr Salahieh |

| Table I | |||

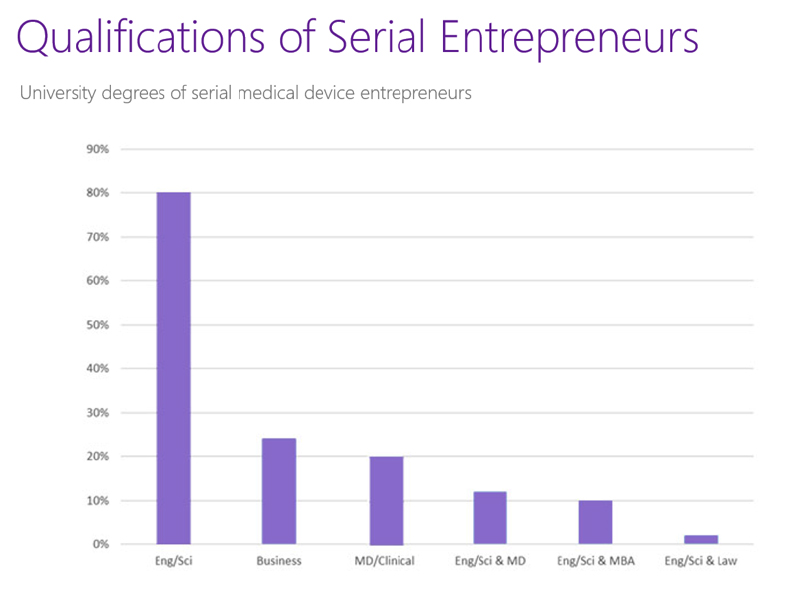

Although the data set is still growing, some very interesting trends have already emerged. For example, on an education level I was surprised to learn that engineering and science degrees are much more common than medical degrees. In fact, 80% of the entrepreneurs in this set studied engineering or science (see Figure 2).

You can see from Figure 2 that studying science or engineering is almost four times more common among serial entrepreneurs than studying either medicine or business.

You may have noticed that the numbers add up to more than 100% since some people have degrees in more than one category. For example, among physician entrepreneurs, more than half also studied science or engineering. The same pattern is observable among business grads. So, if Figure 2 were amended to look at pure business and medicine grads who have science or engineering degree, the results would have been even more extreme.

So far it looks like the Steve Arless model of entrepreneurship is dramatically more common than the Thomas Fogarty model. My own anecdotal experience of 16 years in the medical device development business mirrors this as well. By far, the majority of our start-up clients have technical founders. Most of the doctors are busy being clinicians. From time to time we meet a physician who is willing to dedicate enough time out of the clinic to make a company go.

The next question is how much to study if you choose a technical area. Is it necessary to get a graduate degree?