No software-based technology is completely free of cybersecurity risks and even if you could sell a perfectly secure medical device, vulnerabilities are expected to be found. The good news? Recent FDA policy has incentivized medical device manufacturers (MDMs) to engage in coordinated disclosures of security weaknesses, as well as relaxed regulatory requirements when vulnerabilities are addressed responsibly.1,2

The benefits of vulnerability sharing include arming industry stakeholders with the information they need to assess their devices, minimize their cybersecurity risks, and equip the larger community to proactively mitigate any emerging risks before they can be exploited.

Seth Carmody will be presenting during the 2nd Annual Legacy Medical Device Cybersecurity Conference (A Virtual Event) | September 22–23, 2020 A few MDMs have leveraged FDA’s policy incentives. So far in 2020, Becton Dickinson (BD), Insulet, Spacelabs, and General Electric have all publicly disclosed vulnerabilities.3,4 In a few examples of textbook, coordinated public disclosure, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued a cybersecurity alert for BD’s line of Pyxis medication and supply management devices. BD and DHS described interim protective measures, linked to BD’s product security webpage and stated that BD was in the process of deploying a security update. In another instance, vulnerabilities in Microsoft Windows’ Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) affected Spacelabs Xhibit Telemetry Receivers. The vulnerability was identified and reported, and Spacelabs issued software updates and patches for the affected devices. These are just two of many examples where a vulnerability was identified, either by the MDM or external parties, publicly disclosed, and action taken to reduce the potential for harm.

Collaboration between MDMs and external stakeholders such as DHS and security researchers, demonstrates a shift in culture in which sharing and discussing vulnerabilities is not something to conceal, but a sign of maturity and something to encourage. By changing the culture and narrative surrounding vulnerability disclosures, the healthcare industry can expect to see an increased frequency of vulnerability disclosures from medical device vendors.

What the Data Tells Us

The FDA’s Postmarket Cybersecurity Guidance encourages device vendors to participate in cyber risk information sharing, in which information about security vulnerabilities is shared with the medical device community through a variety of means, such as through FDA safety communications, ICS-CERT, or information sharing entities that share medical device vulnerability information such as the H-ISAC and Medical Device Information Sharing Analysis Organizations (ISAOs).

Security researchers and the Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT) have played a critical role in bringing visibility to vulnerabilities by building a repository for MDMs to communicate with customers. Whether you’re a VP, director, engineering and research professional, or anyone else involved in ensuring cybersecurity best practices are maintained in medical devices, this helps inform decisions around product cybersecurity.

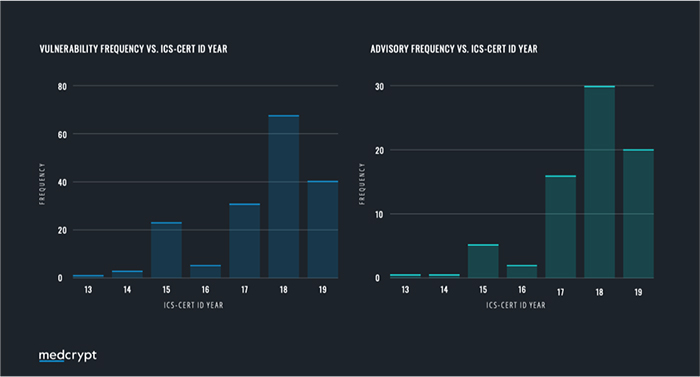

Our team analyzed the ICS-CERT Advisory Database to find all advisories related to medical devices, which were compiled into a report on vulnerability disclosures. Advisories were extracted and divided into two time frames—before and after the FDA Postmarket Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Device Guidance. In total, 78 advisories were analyzed for the timeframe between October 2013 and December 2019, consisting of a total of 179 individual cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

What this data shows us is that since the release of the FDA Postmarket Guidance in December 2016, the number of published vulnerabilities has remained high with an average of 3.94 vulnerabilities being released per month, compared to only 0.95 per month prior to that. A hypothesis presents itself here—has there been an increase in the number of vulnerabilities manifesting in devices? Or has the assistance of the FDA helped the industry move up the cybersecurity maturity curve? It is evident that the increase is attributable to the diligent persistence and willingness to partner that medical device manufacturers have worked to implement.

Regardless, it is apparent that many device manufacturers still have to disclose their first vulnerability despite having the same vulnerabilities that other manufacturers have already disclosed, and it is our prediction that we won’t see a broad increase in disclosures until the FDA or Congress creates an enforcement approach through law.

Public Perception

No company wants to see their name in the headlines for a device vulnerability or recall, especially if that vulnerability could lead to data loss or patient harm. Fear of the repercussions of admitting a vulnerability may leave many medical device and healthcare IT vendors reluctant to openly discuss vulnerabilities found in their products.

This fear is valid, as media can create a negative perception or competitors can use it for market share advantage. This translates into hesitancy to disclose these vulnerabilities, actually making the problem worse.

In today’s world of software-based and complex devices, open communication and vulnerability disclosure should be seen more as a sign of mature security processes. In some instances, a company that discusses its issue openly is usually met with a positive response from the public and media, improving their customers’ trust in the company and in its products. An example of this happened in July of 2018 when LabCorp detected unusual behavior on its network and proactively shut down portions of it. The company was noted for its proactive approach to the problem rather than deemed negligent for failing to disclose information to the public.

The healthcare community is also working to normalize disclosures in unique ways. At DEFCON 27, a notable annual hacking conference that takes place in Las Vegas, the Biohacking Village welcomed attendees to test the security of medical devices in the Medical Device Lab. Medical device vendors were given the opportunity to bring in devices for the participants to test. Upon entering the Medical Device Lab, attendees signed a form agreeing that if a vulnerability in a device was found, they would disclose it to prioritize patient safety and help device vendors improve the security of their devices. The FDA promoted this effort and MDMs more than doubled their participation from 2018, showcasing that the act of engaging external researchers and subsequently going through the process of disclosure is net positive for healthcare.

Looking Forward

Sharing vulnerabilities with actionable information allows hospitals, physicians and patients to take precautionary measures. Identifying a vulnerability and fixing it doesn’t mean a company has necessarily done something wrong; MDMs that actively disclose and address cybersecurity vulnerabilities should be applauded for embracing the disclosure process. While some MDMs have published so-called public disclosure policies, only a handful of those have made public disclosures a priority. Many of MDMs don’t even have public-facing policies yet, which is a signal that these MDMs still have some way to go to accept their cybersecurity responsibility.

While healthtech companies best serve their patients when they develop innovative new technology that is secure by design, vulnerabilities will persist. Robust vulnerability management programs that include coordinated disclosure are a necessity. The FDA has been a leader in emphasizing the importance of coordinated disclosure, yet a more forceful approach may be in the cards so to raise the bar.

References

- FDA. (October 18, 2018) Content of Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices. Draft Guidance.

- FDA. (December 2016) Postmarket Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices. Guidance Document.

- CISA. (February 18, 2020) ICS Medical Advisory (ICSMA-20-049-02). GE Ultrasound Products.

- CISA (January 23, 2020). ICS Advisory (ICSMA-20-023-01). GE Carescape, ApexPro, and Clinical Information Center Systems.